|

Strengthening rural education through the implementation of educational, associative, and rural development initiatives in the Dokabú and Kemberde communities1

Claudia Marcela Mejía-Hernández*

* Master’s Degree in Environment and Sustainable Development, Universidad de Manizales School of Agriculture and Livestock Sciences, Universidad de Caldas, Manizales, Colombia

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Recibido: 13 julio de 2019, Aprobado: 24 noviembre de 2019, actualizado: 18 diciembre de 2019

DOI: 10.17151/vetzo.2020.14.1.6

ABSTRACT. Introduction: Education in Colombia has been established as a fundamental constitutional right guaranteed by the state. Education and its implementation are a shared responsibility in which regional and municipal governments, as well as educational institutions and grassroots social organizations participate to contribute from their field of action to the quality of schooling in their municipalities and rural areas. Aims: To identify the different processes of rural development and associativity implemented to strengthen public education in the indigenous community of Ébera Katio of Santa Teresa’s village and the tri-ethnic community of the city of Santa Cecilia in Pueblo Rico, Risaralda. Methodology: The study is descriptive and cross-sectional, and it was conducted using a qualitative approach. Four study variables, including education–pedagogy, assistance–technical support, actors–allies, and participation spaces, were established to understand executed actions and the aspects to be improved in the development strategies of rural areas. Results: Among the most important findings, we were able to establish the vitality of promoting theoretical and practical knowledge processes in rural areas through the implementation of participative methodologies designed to invigorate the resources of the territory and to facilitate the participation of the Dokabú and Kemberde communities in a municipality in Pueblo Rico, Risaralda. Conclusions: By encouraging theoretical and practical knowledge processes in rural areas, it was possible to complement the required strategies to strengthen education and rural development in the region.

Keywords: associativity, communities, rural development, education, pedagogy, participation

Fortalecimiento de la educación rural por medio de la implementación de iniciativas educativas, asociativas y de desarrollo rural en las comunidades de dokabú y kemberde

RESUMEN. Introducción: La educación en Colombia ha sido consagrada como un derecho fundamental y constitucional, garantizado por el estado. La educación y su implementación es una responsabilidad compartida en la que los gobiernos regionales, municipales, así como las instituciones educativas y organizaciones sociales de base, participan en aras de aportar desde su campo de acción a la calidad escolar de sus municipios y zonas rurales. Objetivos: conocer los diferentes procesos de desarrollo rural y asociatividad empleados para el fortalecimiento de la educación pública en la comunidad indígena de ébera katio de la aldea de Santa Teresa y la comunidad triétnica de la ciudad de Santa Cecilia en Pueblo Rico, Risaralda. Metodos: Se realizó una investigación descriptiva y cruzada con enfoque cualitativo. Se establecieron cuatro variables de estudio educación - pedagogía, asistencia - soporte técnico, actores – aliados y espacios de participación para conocer las acciones ejecutadas y los aspectos a mejorar en las estrategias de desarrollo de las zonas rurales. Resultados: Entre los hallazgos más importantes se pudo establecer la vitalidad de promover procesos de conocimiento teórico y práctico en el área rural, a través de la implementación de metodologías participativas diseñadas para dinamizar los recursos del territorio, así como para facilitar la participación de las comunidades dokabú y kemberde, municipio en Pueblo Rico, Risaralda. Conclusiones: al incentivar procesos de conocimiento teórico y práctico en lo rural, se logró complementar las estrategias requeridas para el fortalecimiento de la educación y el desarrollo rural en la región.

Palabras claves: asociatividad, comunidades, desarrollo rural, educación, pedagogía, participación

Introduction

In Colombia, education is a fundamental constitutional right that is guaranteed by the state. Article 67 of the Political Constitution of Colombia says that education is an individual’s right and a public service that has a social function. With education, the access to knowledge, science, technology, and other goods and values of culture are sought. Although the state must guarantee education in each Colombian region, this responsibility goes beyond being guaranteed by a single national actor to being shared by different actors in each territory. Thus, education and its implementation is a responsibility shared by regional and municipal governments, educational institutions, and grassroots social organizations, to contribute from their field of action to the quality of schools in their municipalities and in rural areas.

Because public rural education faces endless structural and contextual challenges, teaching must be transformed into a process that is more dynamic and adaptable, pursuant to students’ needs and the needs of the teachers who assist them in knowledge qualification at all times. Further, it must take into account the development processes and rural associativity that might arise. In the Colombian rural territories, training processes and associativity are focused on rural development. Actions that improve the living conditions of the local population are implemented through four dimensions: economic, sociocultural, political–administrative, and environmental (Redex, 2016). Consequently, rural lifestyle is positively influenced, answering to the basic needs identified in the rural territory, such as the promotion of agriculture, the protection of natural resources, and the wellbeing of rural communities. Despite the imminent and identified needs to promote processes and policies that strengthen education and rural development in Colombia, close to one-third of the Colombian population (32.7% in the year 2012) is still poor. Furthermore, Colombia is one among the countries with the highest inequality levels in Latin America (Delgado, 2014; OECD, 2013). Institutional weaknesses; availability of teachers for rural areas; and non-availability of cultural spaces, libraries, or sports fields go hand in hand with poor access conditions and land transportation to many of the rural areas in Colombia. These are also reasons why education and rural development in Colombia are quite a challenge.

Therefore, this article aims to identify different participation, associativity, and rural development processes to answer some of the identified issues. It is worth highlighting that the social, economic, and political interactions facilitated throughout this process were key factors for the consolidation of efficient and sustainable educational processes. Thus, the following research question is raised: How can rural development strategies be generated to improve education quality and to strengthen entrepreneurship?

Another goal is to discuss the experience resulting from the agreement implemented jointly with the Ministry of National Education, the government of Risaralda, and Caldas University, which aimed at joining efforts to strengthen formal education of above-age youngsters through pedagogical and flexible strategies that fostered school attendance through pedagogical productive projects as a rural entrepreneurship strategy related to the farming production circuits in the municipality of Pueblo Rico, Risalda.

Materials and methodology

A descriptive and cross-sectional approach was adopted and a qualitative methodology was used, with the aim to know the different rural development and associativity processes implemented to strengthen public education in the indigenous community of Ếbẽra Katio from the Vereda of Santa Teresa and the tri-ethnic community from the corregimiento of Santa Cecilia, in the municipality of Pueblo Rico, Risaralda, Colombia, by selecting and reviewing primary and secondary sources.

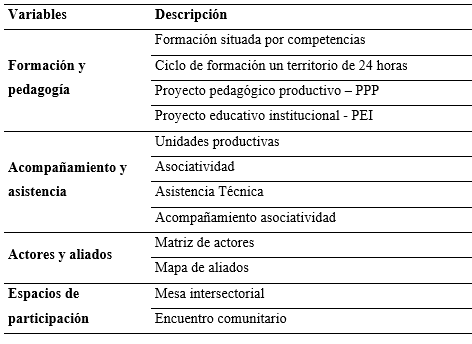

In addition, the research process was developed in two stages to facilitate analysis and subsequent discussion and conclusions. The first stage involved the socialization of study variables, which were oriented toward the agreement components and answer each of the actions developed alongside the implementation phase. These were divided into a. Training and pedagogy; b. Assistance and technical support; c. Actors and allies; and d. Participation spaces. The second stage involved the identification of needs following the socialized information. These were revealed through the different actors to recognize the aspects to be improved in the implementation of future experiences of rural development and associativity. Once the information was socialized and identified, it was later organized according to how each piece of information was presented for its subsequent qualitative analysis to finally share the results. Likewise, it was shown how these aspects can have an impact on the rural public policy guideline construction.

Results and discussion

Through the components developed in the agreement, the results obtained in the study variables have been presented. Table 1 shows the classification of each of the variables, socializing each variable to know their scope in the joint implementation of educational and associative initiatives for rural development.

Table 1. Classification of the agreement’s variables Source: Prepared by the authors, 2020. Note: Adapted from January 10, 2020.

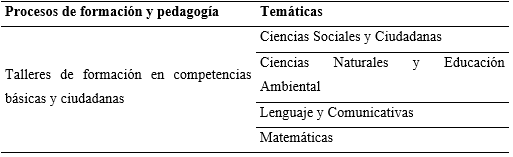

The study commenced with the different training and pedagogy processes facilitated with students and teachers from Dokabú’s intercultural educational institution and the Kemberde community’s Centro Educativo en Bachillerato en Bienestar Rural, Santa Teresa headquarters. The objective of each activity was training honest citizens who can contribute to solving problems in their environment. By using different training and practical workshops, community knowledge was strengthened, and in this manner, the challenges that each community faces in different areas such as farming and economic and social development could be addressed within their territories. Training workshops focused on basic and citizen skills. In workshop development, the methodology used was participation–action, taking into consideration community situations, experiences, and real challenges. In addition, three basic components of this type of citizen skills were considered: knowledge (to know), skills (know-how), and attitudes (know how to be)2. The main aim was to strengthen the basic and citizen skills in two institutions. Dokabú’s intercultural educational institution included teachers and 71 youngsters in the seventh, eighth, ninth, tenth, eleventh, and twelfth grades. The Kemberde community’s Centro Educativo en Bachillerato en Bienestar Rural, Santa Teresa headquarters included parents; leaders; teachers; and 152 students in the sixth, eighth, ninth, tenth, and eleventh grades.

From this training process, it was possible to highlight that students established a direct relationship with the acquired knowledge of the experience gained from their parents, relatives, teachers, and cultural context. Heritage and culture as topics of interest also transcend to other areas of participants’ social lives. Ancient knowledge and wisdom (e.g., shamans, midwives, and medicinal plants) are included in the knowledge that provides sense and identity to their culture. Further, sports were identified as the starting point to execute social projects for personal development. In the same manner, the environment is incorporated as a fundamental factor to identify the type of relations and activities that human beings execute in the natural physical environment to satisfy their needs. The different training and pedagogy processes that were facilitated show the importance of developing flexible pedagogical models. It is key to note that the National Ministry of Education (2010) has established some criteria for the development of such flexible models, setting the grounds for rural education, with special emphasis on farming, livestock, fishing, forestry, and agro-industrial activities, to comply with the necessary criteria for developing training cycles in farming and rural education. Table 2 relates each of the topics and subtopics of the training workshops in basic and citizen skills. An unfocused learning process was an issue that was observed in the group of students of Centro Educativo en Bachillerato en Bienestar Rural; thus, it is necessary to have constant feedback regarding the training process. Moreover, the availability of translators from the Emberá language to Spanish would ease the learning processes in this community because many of the students did not understand some of the Spanish terms. The lack of active participation by the students was highlighted, as well as the nonattendance of some students to the workshops by not showing up at school. Motivating creative reading is necessary so that students reinforce their orthographic skills. In societies where people need to reconcile equity with multiculturalism and identities need to be differentiated, education must incorporate a model where equality coexists with attention to differences (Hopenhayn, 2003). Culture in this learning context determines the social dynamics that students, teachers, and community leaders assume at the time of participating in these pedagogical and productive scenarios. Furthermore, workshops with teachers of the Dokabú’s intercultural educational institution were carried out in topics such as orange economics. Through this, the importance of training teachers in topics of formulation and project management was identified. Likewise, the need to rescue the gastronomic value in their communities, which has been vanishing through time with the new generations, was also identified.

Table 2. Activities, topics, and subtopics of training and pedagogy in basic and citizen skills Source: Focused training proposal, 2019. Note: Adapted from October 20, 2019.

Training workshops focused on socio-emotional skills. The methodology developed was participation–action, which seeks to understand and solve aggression and discrimination in the educational environment, proposing specific pedagogical strategies to prevent aggression and discrimination in schools and promote peaceful coexistence. Therefore, the main aim was to strengthen socio-emotional skills and to implement participative management actions to contribute to improving the school environment in the seventh, eighth, ninth, tenth, and eleventh grades, with a total of 70 students of Dokabú’s intercultural educational institution. While carrying out this type of workshop, three problematic factors were observed inside the educational institution. The first factor was school bullying based on physical looks, school performance, way of speaking, or not being able to complete class exercises on time. The second factor corresponds to conflicts generated because of bullying or intolerance from the parties. In many cases, school bullying is associated with a value loss within the family, and it is recognized as a social phenomenon that already existed a long time ago (Pena & Lamela, 2013). This is related to the third factor identified, which leaves room for physical and verbal aggression, and finally, the family context of the students has a strong impact on the way they relate to their classmates. Table 3 points out each of the topics and subtopics of the training workshop in socio-emotional skills. With regard to the identified needs, it was observed that it is important to promote campaigns that raise awareness among students about the negative psychological impacts that school bullying has on schoolmates who are a direct target of these events.

Table 3. Activities, topics, and subtopics of training and pedagogy in socio-emotional skills Source: Focused training proposal, 2019. Note: Adapted from October 20, 2019.

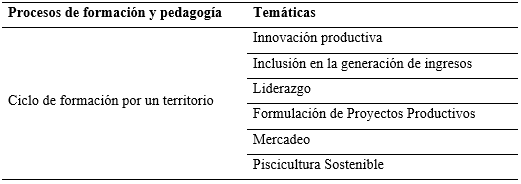

Training cycle for a 24-hour territory. During the mentioned training cycle, the implemented methodology was carrying out through personal meetings in which theoretical knowledge was combined with practical knowledge. In consequence, the knowledge and experience of farming producers were integrated; thus, students were able to prove their knowledge in experimental workshops in the natural environment. The main aim was to train parents, students, and teachers in topics of solidary entrepreneurship, associative entrepreneurship, leadership, productive innovation marketing, and units of solidary economy. Between students, teachers, and parents, approximately 72 persons participated in Dokabú’s intercultural institution, and 115 persons from the Centro Educativo Bachillerato en Bienestar Rural, Santa Teresa headquarters.

One of the positive aspects identified was the commitment that the group of parents that participated in the training showed to learn about entrepreneurship and leadership. In the same manner, they have incorporated the concept of teamwork and the importance of consensus, thanks to which the productive association of parents, teachers, and students—ASOPADE from Dokabú’s intercultural institution—was created. It is worth mentioning that from the exercises done, business ideas to be developed within their project related to their corregimiento arose in topics such as gastronomy, culture, dance, music, sports, and farming. Each person, each rural producer, builds their own reality, through their perceptive capacity, which must be motivated by the intentional transmission processes implemented by the leaders and agencies involved in rural development processes (Chiriboga, 2003). Table 4 presents the topics developed throughout the training cycle.

Table 4: Activities, topics, and subtopics of training and pedagogy in training cycles Source: Training cycle for a 24-hour territory. Note: Adapted from December 02, 2019

Given the identified needs, it is necessary to follow-up training processes regarding legalization and the judicial framework. Parents as participant actors recognize that some of the weaknesses that need improvement are lack of punctuality and the lack of trust in themselves or surrounding institutions. Because of bad life experiences, it was hard for them to trust the new processes of institutional management and rural development. Based on the students, it is necessary to give more training in entrepreneurial projects and marketing strategies. They identified that the entrepreneurial motivations are few, so when launching their products, these can be overshadowed by the lack of sponsorship and better training. Likewise, other strategic alliances are required in public institutions and private companies that facilitate training scenarios for parents, teachers, and students. This highlights the importance of strengthening communication processes for development, which is based on the premise that sustainable development and social change cannot be reached without the conscious and active participation of actors in all the stages of a development process (FAO, 2016). Dialog between different rural actors is essential so that various initiatives for rural development foster a direct impact on the territory and its communities.

Institutional educational project (IEP). Article 14 of the 1860 executive decree of 1994 establishes the guidelines for the IEP formulation and thus mentions that every educational establishment must create and implement, with the participation of the educational community, an IEP that expresses how education goals defined by the law will be reached, taking into account the social, economic, and cultural conditions of their environment (Article 14 of the 1860 executive decree of 1994). Therefore, a follow-up was carried out on the IEP, in the educational institutions of the indigenous communities of Ebẽra Katio in Santa Teresa and the tri-ethnic community from the corregimiento of Santa Cecilia. With regard to the structure and approach of the IEP, alongside the implementation of the agreement, the development of the productive pedagogical projects (PPP) was proposed as a goal to be executed in one of the intended actions for the IEP. Therefore, the executed actions in the PPP are socialized under the IEP’s structure and formulation of each one of the educational institutions and their communities.

Productive pedagogical projects. The PPP are educational strategies that the school develops with the community, taking into consideration entrepreneurship and environmental resource utilization by promoting learning and social development (Cifuentes & Rico, 2016). Four PPPs were established, including two farming production projects, one fish farming production project, and one agro-industrial production project. The first two projects were oriented toward optimizing farming productive systems of subsistence crops (e.g., onions, string beans, yucca, bananas, beans, red tomatoes, and carrots) in Dokabú’s intercultural educational institution and Kemberde’s Centro Educativo Bachillerato en Bienestar Rural, Santa Teresa headquarters. The third project focused on fish farming production with high protein content and of good quality in the Centro Educativo Bachillerato en Bienestar Rural, Educational Headquarters, Kemberde. Finally, the fourth project sought to strengthen the bakery productive project developed with the educational community of Dokabú’s intercultural educational institution. It is worth highlighting that the pedagogical productive projects mentioned are producing and selling by means of the two associations that were created from the agreement3. From PPP’s formulation, it was observed that communities need to focus on the future and to strengthen their entrepreneurial, leadership, marketing, and associativity skills in favor of the PPP. Among the difficulties found are those related to the disparity of calendars for the project’s formulation in each of the communities, along with the unsafe conditions and closure of the Quibdó–Medellín’s road, resulting from the statement of armed strike at the west war front of the National Liberation Army (ELN, in Spanish).

a. Technical assistance and rural extension

The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO, 2016) of the United Nations defines technical assistance and rural extension as important instruments to strengthen family farmers, improving their productive performance, nutritional quality, income, and ultimately, their quality of life. In the case of the alliances generated between the National Education Ministry, Caldas University, and Department of Risaralda, technical assistance was provided to the communities of Dokabú and Kemberde to formalize the leader community organizations of the previously identified productive processes. With that, the development of the different productive activities was guaranteed with the implementation of a legal and judicial framework. Once the qualified processes were identified through seed certification, good production practices, the creation of product improvement plans, and productive chains in the educational institutions linked to the territory, it was possible to give better orientation to organic farming processes and sustainable fish farming.

Associativity. Associativity may be understood as a series of cooperation agreements or mutual contributions among a group, used as a strategy to benefit a business (Esquivia, 2013; López, Pineda & Vanegas, 2008). For this reason, community leaders through their organizations gave a step forward to create as a group, agreements for the development of productive activities. Thus, the process to formalize the association of productive parents, teachers, and students was followed up, as seen in ASOPADE of the Vereda of Agüita of the corregimiento of Santa Cecilia and the productive association of Ebẽra Katio of the Vereda’s community of Santa Teresa, educational headquarters in Kemberde, municipality of Pueblo Rico. Both organizations aimed to meet the food need of the educational community, guaranteeing the production and commercialization of farming and livestock products. Therefore, they currently produce and sell through the pedagogical productive projects mentioned above.

Productive units. Productive Colombia (2017) defines productive units as a company, business, association, producer, or group of persons that perform activities for a profit and who are registered in the Commercial Registry (or tourism national registry) or a legally organized producers organization. Throughout the follow-up generated and from the design of the pedagogical productive projects and associativity processes, the operation of productive units was formalized. The first one corresponded to the productive unit that emphasized on agriculture. Its objective was to promote food safety through the use of two productive systems of subsistence crops (e.g., onions, string beans, yucca, bananas, beans, red tomatoes, and carrots) in the intercultural educational establishment of Dokabú and Kemberde’s Centro Educativo Bachillerato en Bienestar Rural, Santa Teresa headquarters. The unit of fish farming was developed, in which it was created and was launched in the municipality of Pueblo Rico, aimed at the ethnic communities of Kemberde’s educational establishment. In the fourth place, the agro-industrial productive unit (bakery) was developed in agreement with the educational community of Dokabú’s intercultural educational institution. Because of the institution’s limited physical space to accommodate another productive unit, it was decided that the bakery productive project that was already running should be strengthened. Each of these productive units had as their final purpose the commercialization of their products in the School Food Plan (PAE, in Spanish). It is worth mentioning that the methodology implemented for this productive units was that of field schools (ECA, in Spanish), which are a type of non-formal education, where sample families and technical groups of facilitators exchange knowledge, taking experience and experimentation as the starting point (Escobar, Rodríguez, Ramírez & Salinas, 2011) in order to develop the required actions to establish productive units.

b. Actors identification

As previously mentioned, after the development of the agreement, different territorial actors participated, which gave life to each one of the exploited associative and rural development processes; therefore, through the actors’ mapping, it was identified how these relate to each other. It is worth noting that this tool facilitates creating a quick reference of the actors involved in a topic or conflict. Thus, it was possible to go beyond the simple identification or listing of such actors and investigate, for example, their capacities, interests, and incentives (Ortiz, Matamoro & Psathakis, 2016). Consequently, the map of actors and allies was created for the Vereda of Agüita in the corregimiento of Santa Cecilia, as well as the community of Santa Teresa, Kemberde’s educational headquarters, in the municipality of Pueblo Rico, Risaralda in Colombia.

Map of actors. A big part of the inhabitants of the municipality of Pueblo Rico are of ethnic origin, and various indigenous settlements of Emberá Katio, Emberá Chami, and Afro are found. On the one hand, there is the tri-ethnic4 community of Santa Cecilia’s corregimiento, the place where Dokabú’s intercultural educational institution is located. While in Santa Teresa’s Vereda, the indigenous community Ếbẽra Katio represents the Centro Educativo Bachillerato en Bienestar Rural of the Kemberde community. According to the map of actors created, the majority shows a favorable position toward the agreement. The levels of influence vary among high and medium levels, which means that there are leaderships with skills of convening power, managing and legitimacy skills, as well as many with visible political incidence5. Regarding the leaderships identified, it was observed that community leadership is a process that operates at least in two levels of the social aggregate, which is similar to the empowerment concept (Rojas, 2013; Silva & Martínez, 2004). Thus, it is observed that leadership can be analyzed at an individual level and at a community level. The former is represented by leaders that seek a social change and the latter by the use of community leadership skills for the collective good.

Map of allies. The initial purpose was the identification of actors to generate the cross-sectional board, fostering public and private alliances, having as the ultimate goal the strengthening of different rural development processes built alongside the agreement. Thus, it was possible to identify four types of actors that responded by offering financing, associativity, and rural outline training meeting different needs. Therefore, among the previously mentioned, a university network was identified, as well as the SENA, Caldas University, Agriculture Ministry, Ministry of Labor, UMATAS, Chamber of Commerce, Indigenous Reservations, Action Community Boards, ICBF, Entrepreneurial Network, Coffee Committee, Department and Municipal Secretariats, among others. Thus, one of the employed mechanisms to achieve such integration was implementing political instruments that favor the development of public–private alliances (PPA)—in particular, alliances that foster integration between small producers and agro-businesses (Argüello, 2013).

c. Participation spaces

To conclude, it was possible to identify community and cross-sectional participation spaces to develop the agreement. This agreement had a complete follow-up prioritizing the needs established within the School Food Plan (PAE, in Spanish) in the indigenous, African, and mestizo communities. In the same manner, in the community meetings, people socialized the advancement of the agreement sign between the National Education Ministry, the Department of Risaralda, and the Caldas University. All this socioeconomic structure that some authors call social capital and community cultural capital in other cases includes the informal institutions of the rural community and is also an exchange network for goods and information that turns out to be of vital importance to promote participation (Torres, 2007). Facilitating these spaces results in the collective construction of knowledge, as well as socioeconomic and cultural actions that prevail in the Andean region.

Conclusion

The results exhibited in the development of the article provide an answer to the present challenges in the implementation of rural development and associativity strategies by identifying the processes that need strengthening and contributing to the construction of a rural public policy that is coherent and honest with the needs of communities, the territory, and the environment. Based on this, by fostering theoretical and practical rural knowledge processes, the required strategies were implemented to strengthen education and rural development in the region. This was done by promoting and implementing flexible pedagogical models, rural associativity processes, productive pedagogical projects, technical assistance, rural extension; and productive units headed by the different institutional, social, and community actors from the community of Dokabú and Kemberde, municipality of Pueblo Rico, Risaralda in Colombia.

Acknowledgments

Special acknowledgment to the communities of Kemberde and Dokabú, as well as to the Public Institutions and Civil Society Organizations that participated in each one of the created rural development processes, which were essential for this article.

Bibliographic references

Argüello, R. Alianzas público-privadas para el desarrollo de agronegocios. Informe de país: Colombia. División de infraestructuras rurales y agroindustrias. Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Alimentación y la Agricultura de Roma, 2013. [Public-private alliances for the development of agro-businesses. Report of the country: Colombia. Division of rural infrastructures and agroindustries. Organization of the United Nations for the supply of food and the agriculture of Rome, 2013] Available at: Link Accessed on: June 02, 2020

Chiriboga, M. Innovación, Conocimiento y Desarrollo Rural. Segundo Encuentro de la Innovación y el Conocimiento para eliminar la Pobreza Rural, convocado por el Fondo Internacional de Desarrollo Agrícola en Lima, Perú, 24 al 26 de septiembre del 2003. [Rural innovation, knowledge and development. Second meeting of innovation and knowledge to eliminate the rural poverty, summoned by the International Fund of Farming Development in Lima, Peru, 24 to 26 of September, 2003.] Available at: Link Accessed on: February 15, 2020

Cifuentes, J.E & Rico, S.P. Proyectos pedagógicos productivos y emprendimiento en la juventud rural. Zona Próxima, n.25, 2016. Electronic ISSN 2145-9444 [Productive Pedagogical Projects and undertaking within the rural youth.] Available at: Link Accessed on: April 12, 2020

Congreso Nacional de la Republica de Colombia. Decreto 1860 de 1994. Artículo 14. [National Congress of the Republic of Colombia. Executive order 1860 of 1994. Article 14.] Available at: Link Accessed on: September 18, 2019

Delgado, M. La educación básica y media en Colombia retos en equidad y calidad. Bogotá, Colombia. Centro de Investigación económica y social, 2014. 2p. Research study. [Primary and Secondary Education in Colombia, challenges of equality and quality. Bogota, Colombia. Center of economic and social research, 2014.] Available at: Link Accessed on: September 18, 2019

Escobar, J.C., Rodríguez, E., & Ramírez, N. Documento técnico 3: Guía metodológica para el desarrollo de Escuelas de Campo. Apoyo a la rehabilitación productiva y el manejo sostenible de microcuencas en municipios de Ahuachapán a consecuencia de la tormenta Stan y la erupción del volcán Ilamatepec. GCP/ELS/008/SPA. Representación de la FAO en El Salvador, 2011. [Technical document 3: methodological guide for the development of Rural Schools. Support to the productive rehabilitation and the sustainable management of microbasins in municipalities of Ahuachapán as a consequence of Stan’s storm and the vulcanic eruptions of Ilamatepec. GCP/ELS/008/SPA. FAO’s representation in El Salvador, 2011.] Available at: Link Accessed on: May 19, 2020

Esquivia, L.I. La asociatividad como estrategia para mejorar la competitividad de las Microempresas productoras de calzado del Municipio de Sincelejo. Bogotá, Colombia: Universidad Nacional, Facultad de Ciencias Económicas, Escuela Administración de Empresas y Contaduría Pública, 2013. [Associativity as a strategy to improve the competitivity of the microcompanies suppliers of footwear of the municipality of Sincelejo. Bogota, Colombia: National University, School of Economic Sciences, School of Companies and Public accountancy, 2013.] Available at: Link Accessed on: June 02, 2020

Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Alimentación y la Agricultura- FAO. Comunicación para el desarrollo rural. Directrices para la planificación y la formulación de proyectos, 2016. [Organization of the United Nations for the supply of food and the agriculture – FAO. Communication for the rural development. Guidelines for the planning and formulation of projects, 2016.] Available at: Link Accessed on: May 17, 2020

Hopenhayn, M. Educación, comunicación y cultura en la sociedad de la información: una perspectiva latinoamericana. Secretaría Ejecutiva SERIE Informes y Estudios especiales 12. Santiago de Chile, 2003. CEPAL-ECLAC-Naciones Unidas. [Education, communication and cultura in the society of information: a Latin American perspective. Executive secretariat SERIE Reports and Special Studies 12. Santiago de Chile, 2003. CEPAL-ECLAC- United Nations.] Available at: Link Accessed on: January 25, 2020

Ministry of Agriculture of Chile. Seminario Taller Políticas para el Desarrollo Rural en el Área Sur, 1993. [Workshop of Policies for the Rural development in the south area, 1993] Available at: Link Accessed on: May 13, 2020

Ministry of National Education. Directorate of quality for pre-school, primary and secondary education. Subdirectorate of referents and assessment of the educational quality. Criterios para la evaluación, selección e implementación de Modelos Educativos Flexibles como estrategia de atención a poblaciones en condiciones de vulnerabilidad. Bogotá, septiembre, 2010. [Criteria for the assessment, selection and implementation of Flexible educational models as a strategy for the attention to populations in conditions of vulnerability. Bogota, September, 2010] Available at: Link Accessed on: January 15, 2020

Organizacion de las Naciones Unidades para la Alimentacion y la Agricultura. Más allá de la enseñanza: generar conocimientos y fortalecer la extensión rural, 2019. [Organization of the United Nations for the supply of food and the agriculture. Beyond teaching: generating knowledge and strengthening the rural extension, 2019.] Available at: Link Accessed on: May 13, 2020

Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Alimentación y la Agricultura–FAO. Asistencia Técnica y Extensión Rural participativa en América Latina. Principales hallazgos de los estudios de casos en cuatro países, 2016. [Organization of the United Nations for the supply of food and the agriculture-FAO. Technical assistence and participative rural extension in Latin America. Main findings of the studies of cases in four countries, 2016] Available at: Link Accessed on: September 15, 2019

Ortiz, M.A., Matamoro, V. & Psathakis, J. Guía para confeccionar un mapeo de actores bases conceptuales y metodológicas. Cambio Democrático Foundation, 2016. [Guide to design a mapping of actors, conceptual and methodological basis] Available at: Link Accessed on: April 08, 2020

Osorio A.A. La Ruralidad en Colombia: un escenario para debatir y repensar. Manizales, Colombia: Universidad Católica de Manizales, 2017. [Rural nature in Colombia: a stage to debate and rethink] Available at: Link on: March 17, 2020

Pena, I.R. & Lamela, C. El impacto social del acoso escolar, 2013. [The social impact on school bullying] Available at: Link on: September 18, 2019

Red Extremeña de Desarrollo Rural. Concepto de Desarrollo Rural. [Extremaduran net of rural development. Concept of rural development] REDEX, 2016. Available at: Link Accessed on: September 15, 2019

Rojas, R. El liderazgo comunitario y su importancia en la intervención comunitaria. Chile: Universidad del Mar Calama. Psicología para América Latina, [Community leadership and its importance in the intervention of the community. Chile: Mar Calama University. Psychology for Latin America] n.25, 2013, 57-76p. Available at: Link Accessed on: September 18, 2019

Torres, V.N. La participación en las comunidades rurales: abriendo espacios para la participación desde la escuela. Revista Electrónica Educare, [The participation in the rural communities: opening spaces for the participation from the school. Electronic Magazine Educare] n,xii, 2008, 115-119p. Available at: Link Accessed on: June 03, 2020

1 Financed by the inter-administrative agreement No. 129, signed between the Ministry of National Education, the Department of Risaralda, and Caldas University. 2 Specific plan of formation in socioemotional competences 3 ASOPADE and productive association of the Vereda of Santa Teresa, educational headquarters of Kemberde 4 Made by communities Embera Chami, Embera Katio, and Afro 5 Map of actors

Como citar: Mejía-Hernández C.M. Strengthening rural education through the implementation of educational, associative, and rural development initiatives in the Dokabú and Kemberde communities. Revista Veterinaria y Zootecnia. n, v. 14, n. 1, p. 00-00, 2020. http://vetzootec.ucaldas.edu.co/index.php/component/content/article?id=287. DOI: 10.17151/vetzo.2020.14.1.6

Esta obra está bajo una Licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento CC BY

|